World hunger

We need to do some rethinking if we are to overcome the problem of world hunger. Al Imfeld argues in favour of ditching taboos worldwide and overcoming rigid attitudes.

Andreas Kohli spoke with Al Imfeld

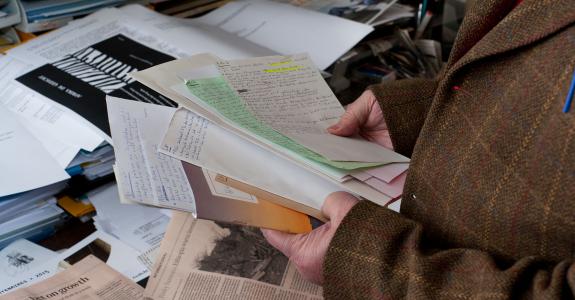

Agriculture is “an art and a struggle”, says Al Imfeld (79). The novelist, journalist, theologist, sociologist and tropical farmer has spent his whole life dealing with social issues, nutrition and agriculture, and he is a holistic and provocative thinker.

Mr Imfeld, you first visited Africa in 1954. Since then you have repeatedly travelled to all of the continents. What do you consider to be the most burning issue as far as nutrition and agriculture are concerned?

We currently find ourselves in the middle of radical change that is manifesting itself mainly at the social level and is also initiating a transformation in agriculture. We are experiencing a world-wide process of decolonisation. Not only men and women, but also flora and fauna are finally getting rights and being liberated. We all have to find a place in this new constellation, and become aware that decolonisation must also embrace our minds and our souls. Things like this take time. But novel developments that could lead to a breakthrough are often suppressed and – worst of all – fundamentally demonised with all means possible.

Can you give us an example?

In Africa, the rural population is pouring into the towns and cities and – as they often say – into the slums. Governments and aid organisations want to send them back to the countryside. A pointless enterprise. Instead of chasing these people away, we should consider creating a combination of town and countryside, and develop urban agrarian models that go beyond mere gardening. Farmers and town planners, urbanists, architects and ethnologists have to start thinking about this task – jointly, and not in isolation from one another.

Are you advocating a new type of polyculture in production and modes of life?

Enlightened Western agricultural approaches claim to be modernising and making farming more scientific by clearing away the bushes and shrubbery, and making everything straight and clean. Fields have been adapted to machines and artificial fertilisers, thus making them monocultural – in other words: without any interaction with other organisms. This kind of agriculture is one-sided, focussing entirely on higher yields and growth.

In the future we will also have small-scale agricultural enterprises alongside large-scale farms. This doesn’t mean, however, that today’s small operations should be preserved at all cost, for they, too, are based on a mindset that is disappearing, as well as a “pre-colonial” concept of the traditional extended family. Furthermore, most small enterprises are also monocultural and subtly suppress newly emerging developments.

What direction do you think agriculture ought to take?

Instead of cultivating vast areas with the same product, farmers – like medieval alchemists – ought to return to mixing and combining: not separating, but uniting. They should plant polycultures, not monocultures. Fields for cereals, followed by clover to allow the soil to regenerate; and, alongside these, trees and hedges for fruits and birds, as well as soil conservation and shade. Field crops (potatoes, manioc and yams) will play a far greater role across the globe. In the Andes, there are more than 3,250 different types of potato. And a Cameroon-German research team under Peter Ay1 has discovered that the Western Cameroons alone have more than 10,000 different types of yams. That leaves an unbelievably huge amount of genetic material to cross and combine.

There is a lot of potential in biological diversity. How can we utilise it?

Both producers and consumers ought to be aware that the present state of affairs is not the final word. Developments and discoveries are still taking place. Plant biologists have spoken of 50,000 plants and trees that could be domesticated to create foodstuffs. The situation is similar with insects and animals. There is this enormous potential that we have, but it is unfortunately partly blocked due to our fear of genetically modified products. On top of that there is this economic lunacy that everything a certain company cultivates or refines has to be patented. When it comes to foodstuffs, all patents ought to be banned in the contemporary ethical sense: no natural product belongs to any one company.

Self-sufficiency or open borders: what’s a good balance?

As long as the old concept of nations is interpreted narrowly, the demand for self-sufficiency is going to result in some sort of stupid nationalism. If every single nation on this planet were to insist on it, we would have “fenced-in famines”, because we can only overcome hunger in the world if we have open borders, trade and an open exchange of comestible goods.

You mean global free trade in line with the WTO guidelines?

No, my demand has nothing to do with free trade as currently defined by the WTO. My concept has to do with decolonisation and not with the rampant trade of multinational food manufacturers who have suddenly started joining the ranks of farmers and agriculturalists. In other words, we must learn in theory and practice to distinguish between the traditional small-scale farmer and the decolonised or emancipated farmer. Or to distinguish exchanges of goods from a type of trade that disregards traditions. Globalised trade has destroyed the entire agricultural sector in Africa, because “cheaper” can also mean poisons and destruction.

There are those who claim that humankind would starve without industrial agriculture.

That’s nonsense! Let’s be honest: industry wants to make money with agriculture and food. And it is industry’s right to do so as long as it doesn’t apply concealed colonial methods. Patenting seeds and forcing farmers to use them is a colonial method. Despite this, I am not denying industry its right to exist as long as it encourages human and socio-human cooperation, as well as greater openness and objectivity. Nowadays, agribusiness is too well represented in all of the UN organisations (FAO, WTO), development organisations (IMF) and even at the universities. With its power, it is destroying agrarian cultures and farming.

Shouldn’t we then be focusing far more on other forms of agriculture – such as organic farming?

I am sometimes disturbed by the fact that other forms of agriculture – probably resulting from frustration – act in an almost fundamentalist way towards agribusiness and react with nothing but denunciations. Bio or organic farming is just another type of agriculture. To my way of thinking, organic farming fails to sufficiently include the social element.

What do you mean?

Genuine and good organic farming is impossible within the framework of traditional small-scale family systems, because the personal freedoms of those concerned would suffer considerably under the workload and from being permanently tied down.

It will therefore be necessary to include cooperative models, because today everyone also has the right to leisure time, travel and wellness. As early as the 1960s, some twenty farmers, economists, ecologists and sociologists laid the foundations for the eco-farming movement2. They tried out this holistic approach, which stimulates interaction between eco- and social systems, on Mount Kilimanjaro and later in Rwanda. In the meantime, the movement has spread across the globe and its ideas are now being implemented in Japan, India, Brazil, the United States and, to some degree, in Europe, too. Eco-farming establishes networks between agricultural and social systems, and attaches great importance to sustainability. It applies the art of crop mixing.

Farmers produce foodstuffs so that people can eat. Eating is an existential necessity. What do you think about food in the future?

Nowadays it is a question of coming together globally to address the topic of food and becoming acquainted with other cultures. Some claim that Africa has a hunger problem because Africans have too many taboos about eating. Ethnologists have documented over 1,000 taboos in Africa, many of which serve to protect people from their neighbours or to help them to stand out from the surrounding small nations.

Food, however, can help people to respect one another as well as create peace. We eat not only to satisfy our hunger, but also because we want to appreciate one another as neighbours. “We eat the fruits of the world” could be our motto – as well as a basis for respecting other cultures. We should no longer say, “I’m not going to eat that!” but, “I’ll eat that, too.” Food makes us feel at home. New foods help create a sense of home. To put it differently: when you settle in a new place, you need to get used to eating new foods to feel at home.

You are pleading for a diversity of foods and for an increase in the choice of foods.

To protect ourselves from possible famines, we must also ensure that our diets are not monocultural. Variety is a basic feature of every food culture. Our tastes need to be redirected and cultivated differently. We can also become accustomed to a certain taste.

We are now in the process of extending our range of foods. The idea that weeds can be turned into salad is something new. Many of the peoples on this planet have never seen salad or view it, in much the same way as my father did, as animal fodder. The significance of tea is still largely unrecognised and could be expanded. Coca Cola and Pepsi aside, the best drinks can be developed from mixtures. We humans need variety in our meals. Always eating the same things puts us off, and spoils our sense of joy and life. These days we no longer live in seclusion from others: we are subject to influences from all over the world.

In the light of your many years of experience, how do you see the future?

To my way of thinking, we need to find a new direction. Anyone who wants to live a healthy life needs to know that agrarian culture and agriculture are an art and a struggle. But anyone who sees their deeper meaning gradually develops this mentality, which evolves into a form of spirituality.

1 Prof. Peter Ay, “The Biological Diversity of Yams in Western Cameroon”, 1979, IITA (International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Ibadan, Nigeria)

2 “Eco-farming” was developed in the early 1970s by the biologist Professor Kurt Egger and the social scientist Professor Bernhard Glaeser (chairman of the German Society for Human Ecology/ DGH). Eco-farming aims to use the soil in a sustainable fashion and to preserve its fertility. In this way, the soil can be used for long periods with minimal capital investment. Harvests remain relatively stable, making it possible to improve the social and economic situation of small farmers. “Permaculture” pursues a similar concept. Eco-farming, in contrast to other ecological movements, includes societal and social aspects.