Food security

Equal shares. Food security and rationing

Engraving showing the distribution of bread to immigrants arriving in England in 1709, Neu eröffneter Historischer Bildersaal, Germany, 1727, p.526, AL4066

The concept of ‘food security’

Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life." World Food Summit, Rome, 1996

The concept of ‘food security’ emerged in 1974 at the first World Food Conference, organised in response to famines around the world. It referred to the global governance needed to guarantee “The availability at all times of adequate world food supplies of basic foodstuffs to sustain a steady expansion of food consumption and to offset fluctuations in production and prices.” In response, a spectacular production effort, mainly of cereals, sought to guarantee the availability and stability of supply at world level.

In 1996, the World Food Summit in Rome broadened the definition of food security to include physical, social, and economic access to sufficient and nutritious food for all. The issues have evolved over time to include questions of equitable access and resilience to contemporary crises. Since then, food security has been assessed at different levels: individual, family, community, national, and continental. Even in the wealthiest countries, parts of the population can suffer from hunger or malnutrition.

While an average of nine million people die each year from hunger and malnutrition, the dominant risk factors are now environmental change and armed conflict. War in a major food-exporting country, such as Ukraine, or global climatic phenomena, such as El Niño, affect many countries around the world. Protracted armed conflicts, such as those in Yemen, Syria, Gaza, and Sudan, leave entire populations food insecure. Food security is a global issue that depends on political stability, infrastructure, and the management of natural resources, especially water and land.

Switzerland has long attached great importance to food security

It is committed to meeting the nutritional needs of its population in all circumstances. Its mountainous terrain and limited agricultural land have historically posed a challenge to the production and availability of food, with notable episodes of famine such as that of 1816. In response, the Swiss authorities implemented self-sufficiency policies to reduce dependence on food imports. Agricultural reforms sought to increase productivity and modernise practices. One of the world’s first agricultural teaching and research establishments was already founded in Hofwil (Bern) in 1808. However, during the two world wars, Switzerland faced shortages and introduced rationing systems for a total period of fifteen years! After the war, subsidies and support programmes stimulated national production and stabilised prices. The government now promotes sustainable agriculture and supports research to meet new challenges, such as the impact of environmental changes on production.

« Kornhaus », Zürich, Switzerland © Arkitekturfotograf Rasmus Norlander

Standing 118 metres high and capable of storing up to 40,000 tonnes of grain, the Swissmill is the second highest tower in Zurich, as well as the world's tallest working grain silo. This building embodies the strategic role of grain reserves in a country's food security.

The moral underpinnings of a principle of food rationing

The moral underpinnings of a principle of food rationing are based on considerations of equity, distributive justice, and solidarity. In times of crisis, such as wars, natural disasters, or pandemics, food resources are often limited and demand exceeds supply, which can lead to famine. The aim of rationing is to ensure that everyone has fair access to the food they need to survive and stay healthy. This principle is based on the idea that all people have a right to adequate food and that resources must be distributed in a fair and equitable manner, taking into account the basic needs of each individual. For some, this means making individual sacrifices for the common good in order to minimise suffering and injustice. Ultimately, a principle of food rationing in times of crisis expresses the universal values of human dignity and collective responsibility to ensure that no one is left behind and that everyone has equitable access to food resources.

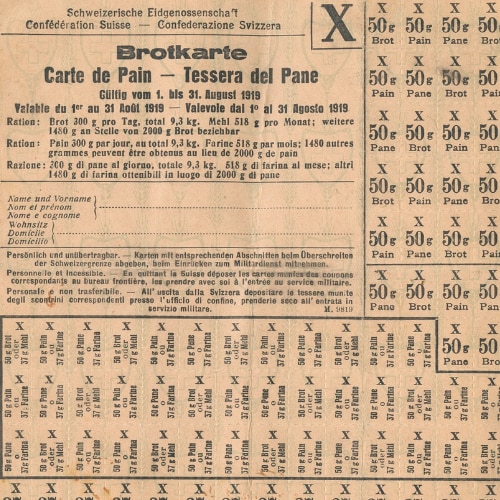

Bread card, Steffisburg, Bern, Switzerland, 1919, AL4070 © Alimentarium

The current global food system is based on agricultural production that is overall unsustainable

Paradoxically, it is one of the main threats to food security. Overfishing and modern agriculture and livestock production are undoubtedly the singlemost historical causes of the exponential loss of biodiversity, disrupting the natural balances essential to the resilience of crops, soils, and ecosystems in general. This biodiversity crisis, now referred to as the ‘sixth mass extinction,’ is already having a direct impact on food production. Even more than climate change, which is already significantly reducing crop yields, the collapse of biodiversity is threatening the ‘ecosystem services’ that have sustained agriculture for millennia, including crop pollination, pest control, maintenance of soil fertility, the functioning of the water cycle, and the plant nutrient cycle. Added to this is the impact of extreme meteorological phenomena, which are causing increasing crop losses every year on all five continents.

Spraying herbicide © Getty Images Signature

The Alimentarium’s collection contains interesting evidence of periods of hunger and famine

Here, we are presenting objects from Switzerland and elsewhere that bear witness to these difficult times. A plaque recalls the inflation in the price of staple foods during the famine of 1816, which affected Switzerland as well as many other countries around the world. A military biscuit originates from the refuge in Switzerland of 87,000 hunger stricken soldiers of General Bourbaki’s French army in January 1871. A fragment of bread is a souvenir of the siege of Paris in 1870–1871, an event during which not only cats and dogs had to be eaten, but also the animals in the zoo! A piece of bread bears witness to the hunger of the ‘French evacuees to Germany’ in 1914. Various documents illustrate the fifteen years of food rationing in Switzerland during and after the two world wars, including wartime recipes and domestic preservation jars. Survival rations, such as those found in civil defense shelters, evoke the role of the state in preventing and managing the risk of food shortages. There are also ‘ersatz’ foods (from the German for ‘substitute’), cheaper, lower-quality products consumed in the expectation of a return to abundance.