Feeding the World in the Anthropocene

Food that can feed 10 billion people by 2050.

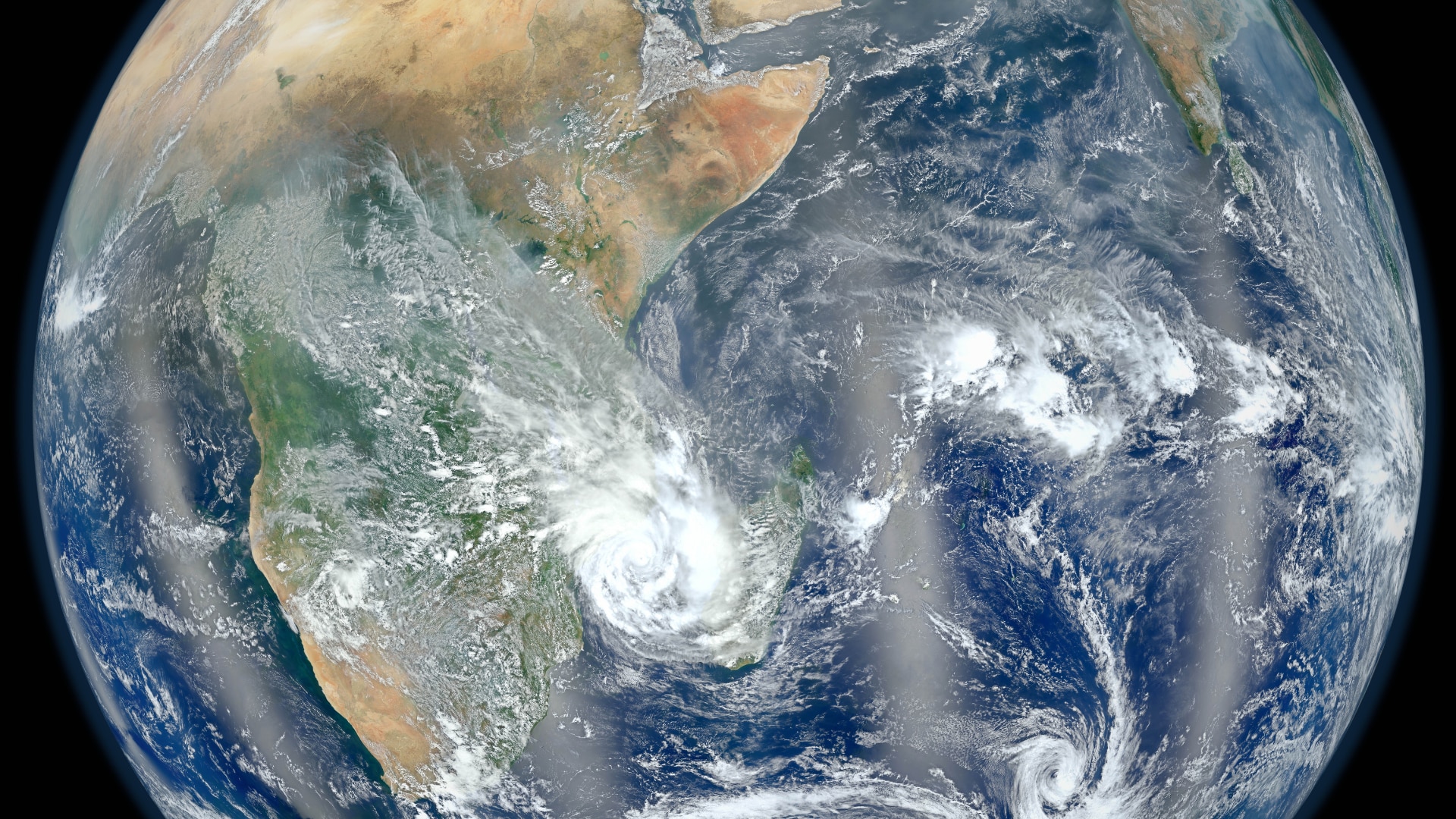

The blue planet, Photo EUMETSAT / ESA © ESA

The mission of the consortium of scientists that made up the ‘EAT-Lancet Commission’ in 2019 was to design a global diet that would reconcile global health and the preservation of biodiversity by 2050. The Commission radically put the challenges facing the food system into perspective and called for a ‘Great Food Transformation.' It pointed to the profound changes required in food production and consumption to meet the challenges of malnutrition, climate change and biodiversity loss.

The main health goals are to adopt a predominantly plant-based diet and to significantly reduce consumption of red meat, refined sugar, and palm oil. This diet, known as the ‘Planetary Health Diet,’ is based on nutritional recommendations that aim to prevent many diet-related diseases, combat the obesity that currently affects 25% of the world’s population, and ensure that more than 800 million people who are currently undernourished have access to sufficient food.

On the environmental front, this means transforming farming practices to halve greenhouse gas emissions, preserving water and arable land resources, adopting regenerative methods for water and soil, and limiting food loss and waste to preserve natural ecosystems. The EAT-Lancet report stresses the need to anticipate food production capable of feeding 10 billion people by 2050, i.e. 25% more people than today, while respecting ‘planetary limits,’ in particular by preserving two-thirds of agricultural land for food crops rather than for intensive livestock farming or for non-food crops.

Andries Beeckman, A Market Stall in Batavia, 1640 – 1666, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, SK-A-4070 © Rijkstudio

Water, a Vital Nutrient

Water is a food that no human being can go without for more than a few days without risking his or her life. Water plays a key role in the body, particularly in digestion, transporting and absorbing nutrients, and regulating temperature. All the body’s organs and tissues need to be constantly hydrated to compensate for the regular loss of water through urine, faeces, sweat, and respiration. On average, an adult needs to consume two to three litres of water a day through both drinking and eating.

The oldest wells dug by humans have been discovered in China and Mesopotamia. They date from the Neolithic period, 8,000 to 10,000 years before today. Then came canalisation and irrigation techniques, dams and reservoirs, and then, in Roman antiquity, the construction of aqueducts and drinking water distribution systems.

Access to drinking water is unequal around the world and is often the number one issue for food security. According to a review of scientific evidence published in Science in 2024, 4.4 billion people do not have regular and guaranteed access to safe drinking water. It can be a question of quality: either the water is contaminated by microbes, leading to diseases such as cholera and diarrhoea, which cause half a million deaths a year in developing countries, according to the World Health Organization; or it is polluted by agricultural and industrial activities, domestic sewage or lead from old distribution networks, which is more common in developed countries. It can also be a question of availability: in sub-Saharan Africa, more than 60% of the rural population has no guaranteed access to water; in India and China, megacities such as Chennai, New Delhi, Beijing or Shijiazhuang suffer water shortages every year.

Photo Josfor © Getty Images Pro

Salt, an Essential Nutrient

Humans have been producing salt for food for about 8,000 years and the Egyptians used it to preserve food 5,000 years ago. Depending on the region, salt was extracted from salt lakes and marshes, mines, and salt springs. Salt was also made from the ashes of certain plants. Now an essential condiment in every culinary culture, salt has left its mark on history. It supported the development of trade routes and the emergence of cities such as Salzburg, the 'salt city.’ In the Roman Empire, salt was such a valuable resource that it was sometimes used to pay soldiers, hence the word 'salary.’ Its production and use has shaped societies on every continent and played a key role in world economic and cultural history.

Salt is vital for the proper functioning of the human body, particularly for fluid regulation and nerve transmission. However, too much salt can lead to health problems, including high blood pressure and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends a maximum salt intake of 5 grams per day. The global average is more than 10 grams per person per day. In Switzerland, it is 9 grams per day, 75% above the recommendation! The main sources of salt in food are: bread and bakery products (27% of intake); starchy dishes and foods (20%); meat and cured meats (13%); sauces (9%); cheese (8%). Salt used in food, whatever its origin, is a crystal of sodium chloride (NaCl). Depending on the natural source, salt may contain trace elements that are essential or beneficial to health, such as iodine (Io) in sea salt, iron (Fe) or magnesium (Mg).

Quang Nguyen Vinh © Pexels

Animal Proteins

For more than two million years, mankind has relied on hunting for animal protein. The domestication of livestock, on the other hand, began around 10,000 years ago during the ‘Neolithic revolution.’ Livestock farming for meat production surged from the 19th to the 20th century, driven by the industrial revolution, urbanization, rising purchasing power, and a remarkable population increase. However, among the variety of birds and mammals available on the planet, only thirty species are commonly consumed, including chickens, pigs, cows, and sheep. While fishing appears to have been discovered later, around 50,000 years ago, fish now plays a significant role in the global diet, constituting an essential source of protein for over three billion people.

Eating too much meat has a negative impact on human health, increasing the risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and certain cancers. Meat production also contributes to deforestation, biodiversity loss, and greenhouse gas emissions. Industrial fishing, for its part, not only overexploits fish stocks, but also destroys marine habitats and disrupts marine ecosystems. Together, these practices exert untenable pressure on natural environments and compromise the planet’s environmental sustainability.

Frans Snijders, Larder Still Life, ca 1616 – ca 1625, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, SK-A-379 © Rijkstudio

Vegetable Protein?

Proteins are the building blocks of all living things. They are therefore found in all foods, including vegetables, but in higher amounts in nuts and legumes. Dried peas and lentils originate from the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East, where they have been eaten for around 10,000 years, while soya has been grown in China for over 4,000 years. Beans and peanuts come from South America, while various nuts, such as almonds, hazelnuts, pistachios, and walnuts, have been harvested in Central Asia and the Mediterranean for thousands of years. Thanks to the cultural and commercial exchanges that have marked the modern era, these plants have spread all over the world.

Tree nuts (walnuts, hazelnuts, almonds…) and legumes (beans, peas, peanuts…) are an essential part of a healthy diet. Rich in complex carbohydrates, protein, micronutrients, B vitamins, and fibre, legumes help prevent heart disease, diabetes, and obesity. The digestibility of their proteins for humans is, however, relative, depending on the variety and method of preparation. Growing them can improve soil fertility by fixing nitrogen, reducing the need for chemical fertilisers. To produce the same amount of protein, the culture of legumes requires much less water and energy than meat production, emit fewer greenhouse gases and therefore contribute to environmental sustainability. So, eating legumes is good for health and good for the planet.

Melchior d’Hondecoeter, Forest floor with Birds, Butterflies, and a Lizard, ca 1668, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, SK-A-169 © Rijkstudio

Milk, Yoghurt, Cheese!

Archaeological evidence from the Middle East and Europe suggests that humans have been drinking milk and making cheese for around 11,000 and 7,000 years respectively. It was the domestication of cows, sheep, goats and, more recently, camels that led to the development of milk production. Although the first traces of cheese were found in the Fertile Crescent region of the Middle East, the practice subsequently spread to Europe, Central Asia, and North Africa. Camel milk is particularly important in arid regions such as the Middle East and parts of Africa. Milk and its derivatives are an essential part of many food cultures around the world.

Dairy products such as milk, butter, and cheese are rich in calcium, high-quality protein, vitamin B12, and vitamin D, which are essential for healthy bones, muscles, and the nervous system. However, on a global scale, their production poses significant environmental challenges, including greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation for pasture expansion, feed production, and intensive water use. In addition, intensive dairy farming raises the issue of animal waste management, which is a major source of air, soil, and water pollution.

Floris Claesz van Dijck, Still Life with Cheeses, ca 1615, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, SK-A-4821 © Rijkstudio

Vegetables in every Colour!

Around 10,000 years ago, humans began growing a wide variety of vegetables in different growing centres around the world. For example, carrots were grown in Mesopotamia, beetroot in Europe, and cabbage and spinach in Asia. However, the number of vegetables grown worldwide represents only a small fraction of the 300,000 or so known plant species, of which 30,000 are potentially edible. Only about thirty of these form the basis of the world’s diet today... yet there are thousands of varieties of the latter! The history of vegetable growing goes back thousands of years, with genetic selection and the movement of species from one region to another.

Regular consumption of a variety of vegetables, including root vegetables, green vegetables, orange vegetables, and red vegetables, has numerous health benefits, particularly due to their richness in vitamins, minerals, fibre, and antioxidants. The health risks associated with eating vegetables are extremely rare and insignificant compared to other foods. Although their cultivation, characterised by a high level of biodiversity, has been sustainable for thousands of years, intensive and extensive production can now have a negative impact on ecosystems and biodiversity, particularly through the excessive use of pesticides and fertilisers and the artificialisation of land. It is important to promote sustainable farming practices to minimise these impacts, while encouraging a diet rich in vegetables to support long-term human and environmental health.

Adriaen Coorte, Still Life with Asparagus, 1697, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, SK-A-2099 © Rijkstudio

Taros, Potatoes, and Jerusalem Artichokes...

The cultivation of tubers such as potatoes, Jerusalem artichokes, taro, and cassava began several millennia ago in various centres of agricultural development around the world. Potatoes originated in the Andes, where they have been grown for over 9,000 years. Taro is traditionally grown in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Jerusalem artichokes have been domesticated in North America, while cassava, originally from South America, has become a staple food in sub Saharan Africa. These tubers are an important source of calories and essential nutrients in many parts of the world. They have formed the staple diet of many societies in varied and sometimes difficult climates.

Potatoes, Jerusalem artichokes, taro, and cassava play an important role in the global diet as rich sources of carbohydrates and essential vitamins. Potatoes are hardy and are grown in a wide range of climates and soils. Jerusalem artichokes, adapted to temperate climates, and taro, in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, are also staples in local diets. In sub-Saharan Africa, Cassava is an important source of calories in arid regions, although its yield is usually quite low. When it is not intensive monoculture, the cultivation of these tubers has agronomic benefits, such as soil conservation and disease resistance, which contribute to local food security.

Suze Robertson, Peasant Woman Peeling Potatoes, 1875 – 1922, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, SK-A-4696 © Rijkstudio

A bounty of Fruit

Humans began domesticating fruit trees and growing fruit for consumption around 10,000 years ago, during the Neolithic Revolution. Among the first fruits to be cultivated and used for food were figs in the Middle East, dates in North Africa, olives in the Mediterranean, and grapes in Eurasia. The practice quickly spread to other continents, where indigenous fruits such as mangoes in Southeast Asia, bananas in Papua New Guinea, and pineapples in South America were domesticated and incorporated into local diets. Fruit growing and processing has thus diversified, fulfilling both nutritional and culinary roles for populations around the world.

Regular consumption of fresh fruit is essential for health as it provides vitamins, minerals, fibre, and antioxidants. It helps to strengthen the immune system, prevent cardiovascular disease, and maintain optimal weight. Traditional fruit production techniques respect ecosystems by diversifying crops, ensuring crop rotation, and using biological methods to control pathogens and pests. They promote biodiversity, protect the soil, and reduce the use of chemicals. Conversely, very large-scale intensive fruit production is synonymous with deforestation, soil and water pollution from pesticides, and extremely high water use, all of which threaten environmental and food sustainability, often in the short term.

Martinus Nellius, Still Life with Quinces, Medlars, and a Glass, 1669 – 1719, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, SK-A-1751 © Rijkstudio

Cereals

Emblematic products of the ‘Neolithic revolution,’ the five main cereals consumed worldwide – maize, wheat, rice, barley, and sorghum – were domesticated at different times, between 3,000 and 10,000 BC, and in different regions of the world. Wheat was domesticated in the Middle East, rice in Asia, maize in Central America, barley in the Middle East, and sorghum in Africa. Together, these cereals provide a significant proportion of the world’s calorie intake: wheat, maize, and rice, for example, account for over 40% of it, while barley and sorghum are essential components of many smaller diets.

Eating cereals is good for your health because they are rich in complex carbohydrates, fibre, B vitamins, and minerals. They provide lasting energy, aid digestion and help prevent cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. However, the refined cereals used for white bread, pastries, and pasta, as well as corn tortillas and nachos, lack fibre and nutrients, leading to weight problems, blood sugar spikes, and metabolic diseases. The germ and bran have been removed from these cereals for reasons of preservation and ease of use. For a balanced diet that maximises nutritional benefits while minimising health risks, it is crucial to favour diversity and wholegrain cereals, for example quinoa, oats, buckwheat, spelt, rye, etc.

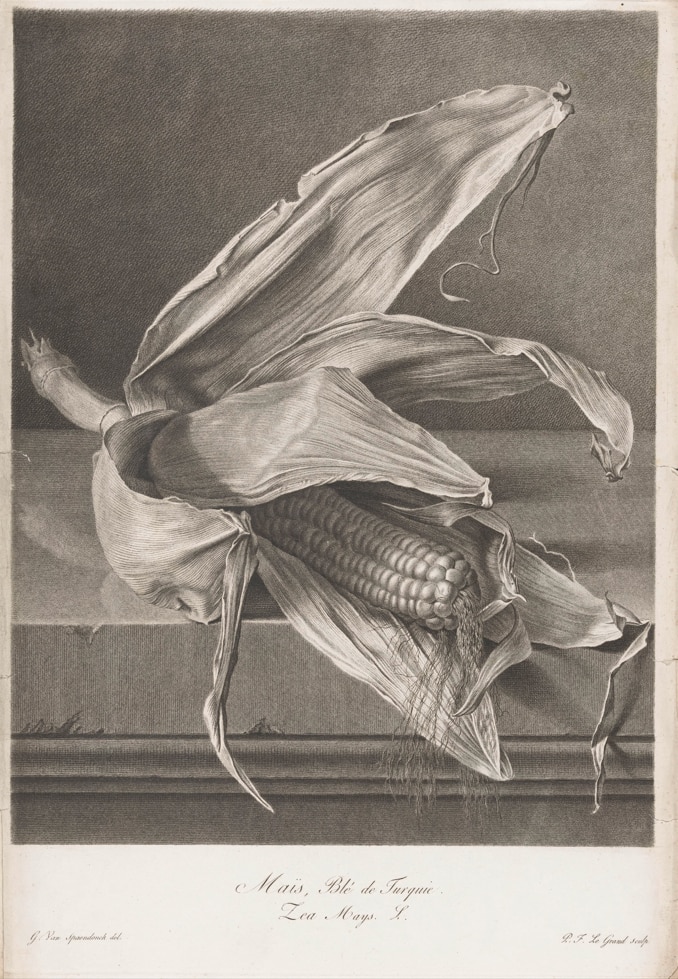

Pierre François Legrand after Gerard van Spaendonck, Maize, 1799 – 1801, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, RP-P-1909-4231 © Rijkstudio

Butter, Oil, and Fats

Olive oil was first produced around 8,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East. It then spread to the Mediterranean, where it was used as early as 6,000 years ago by ancient civilisations for its culinary and dietary properties. Edible oils are extracted from a variety of seeds, nuts, and legumes. Sunflower seed oil was produced in North America 5,000 years ago. It has only been produced in Europe and Russia since the 19th century. Palm oil, which originated in West Africa, spread around the world in the 20th century because of its high yield, but is controversial because of the devastating effects of its cultivation on tropical forests. Fish oil, rich in n-3 fatty acids, has been an essential part of the coastal diet for centuries. Butter, lard, and tallow, which are animal products, have been important sources of fat in regions where livestock have been reared. Together, these fats and oils are important components of the global diet, providing essential calories and nutrients for human health.

Although all oils have the same calorie content, their health effects vary considerably, especially when cooked at high temperatures. Olive oil, rich in monounsaturated fats, is good for the heart, even when cooked at high temperatures. Sunflower oil, a source of polyunsaturated fats, can reduce cholesterol but produces harmful compounds at high temperatures. Palm oil, rich in saturated fats, increases cardiovascular risk, especially when heated. Fish oil, rich in n-3 fatty acids, is good for the heart and brain, but its unstable fatty acid content means it needs to be cooked gently. Butter, lard, and tallow, rich in saturated fats, produce toxic compounds when heated and should be eaten in moderation. The choice of oils and fats is therefore crucial, not only in terms of their fatty acid composition, but also their stability at high temperatures, in order to minimise their potential harmful effects on health.

Anonymous, Padang Halaban. Harvest department. November 1928, 1928, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, NG-1992-4-1-41-3 © Rijkstudio

Added Sugars

Humankind has been producing and consuming sugar in very small quantities since ancient times, with the first forms derived from sugar cane, which originated in Papua New Guinea and has been cultivated in India for over 2,500 years. Cane sugar spread to the Middle East thanks to the Persians, then to the Mediterranean basin during the Arab Muslim conquest in the 7th century, before reaching the rest of medieval Europe thanks to the Crusades. In the 16th century, the creation of slave sugar plantations in the American colonies led to an explosion in the production and distribution of cane sugar. In the 19th century, the boom in sugar beet production in Europe diversified the sources of sugar, which was then increasingly refined, making it both more attractive and more accessible worldwide.

Excessive consumption of sugars and their many industrial derivatives found in processed foods and sweetened drinks has a serious impact on global health. They contribute to epidemics of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, as well as tooth decay. According to the World Health Organisation, around 43% of adults worldwide are overweight or obese, and 10% are already affected by diabetes, mainly due to a diet too rich in sugars. This overconsumption leads to high public health costs and significantly reduces healthy life expectancy. In addition, sugar crops, which are intensive monocultures, as well as water-intensive in the case of the sugar cane, have a major impact on the environment and compete with food crops that contribute more to a healthy diet.