Nursing in Art

Depending on one’s view, the theme of nursing can arouse affection or be unsettling. How did artists from different periods of history choose to present it?

Various mythologies recounting the origins of the universe, from African tales to Indian fables and Greek legend, present milk as an elemental bodily fluid, a creator of worlds and giver of life. So it was believed, for example, that the myriad of stars in the universe was sown by the milk of Greek goddesses (galaktos). The Milky Way was said to have been created by milk literally spurting from the bosom of Hera, the queen of the gods(1). Whereas the origins and maternal legacy of nursing appear fairly straightforward and its vital role is obvious, a brief stroll through the history of art reveals the diverse symbolism attached to nursing, a symbolism often strange, occasionally troubled and shrouded in eroticism. What indicators can we use to get a clearer picture?

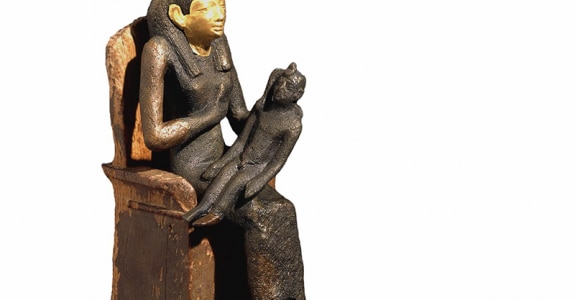

The iconographic nature of the ‘Nursing Madonna’ stems from ancient Egypt(2). There are countless representations of Isis nursing Horus, a theme addressed so often that today’s museums are literally brimming with such statuettes(3). They belong to the most ancient representations of the nursing mother. Several thousands of these statuettes have been recovered, with Isis acting as an important figure of worship in the first millennium BC, a period in which the Egyptians were accustomed to producing bronze statues of their gods and readily offered them as homage on pilgrimages to holy sites. The goddess was therefore at the centre of a religious fervour that spread across the entire Mediterranean Basin(4). Isis, the wife and sister of Osiris, was said to have saved her son after a snake bite thanks to the divine nectar that she made him drink. The statuettes illustrate the unique schematics of Egyptian art. The figures are presented in perpendicular planes and thus appear somewhat unrealistic. Isis offers her bosom with her right hand, while supporting the child’s head with her left.The child also appears to tense up or retreat from the offering rather than hasting to suckle. However, whereas the ritualised and hieratic posture varied little from one group to another, it ushered in an iconographic tradition that would subsequently endure into the Gallo-Roman and Christian eras, in the form of mother goddesses and nursing virgins.

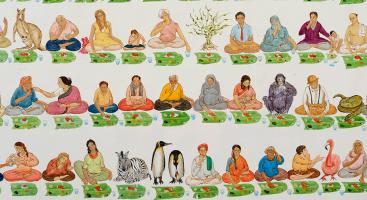

Gods are purely the personification of our personal limitations, which is why it should not surprise us to see them used to depict one of the more unsettling aspects of nursing – human animality. Zeus feeding from the goat Amalthea on the island of Crete, Telephus drinking from the udder of a doe, Romulus and Remus being fed by a she-wolf: These are the mythological equivalents of a custom witnessed in various periods of history, from Egypt to the Scythians(5). Research into substitutes for maternal milk (goat’s milk, cow’s milk, asses’ milk, whether diluted or pure) is thus inseparable from the history of nursing and is often motivated by economic factors, time restraints or shortage of wet nurses. As proof of this century-old practice, in 1816 the German physician and philosopher Conrad Zwierlein published The Goat as the Best and Most Agreeable Wet Nurse, the title of which alone resonates like a proclamation. In it, Zwierlein went to great lengths to demonstrate the superiority of suckling from goats considering the constraints affecting feeding infants(6). It was somewhat like making the best of a bad situation. Over the centuries, wet nursing and resorting exclusively to cow’s milk caused a number of problems, undoubtedly contributing to the alarmingly high infant mortality rate witnessed up until the 19th century. Hence, it came as good news when experts realised that goat’s milk could enhance an infant’s nursing routine, but should not be a replacement for mother’s milk. Thus, in his 1873 publication Physiologie de la chèvre-nourrice (The physiology of wet nursing with goats) the French physician Auguste Boudard explained that it was a method of compensating for the harmful effects of when mothers were often forced to abandon nursing, but that the latter remained in all respects the most desirable option(7).

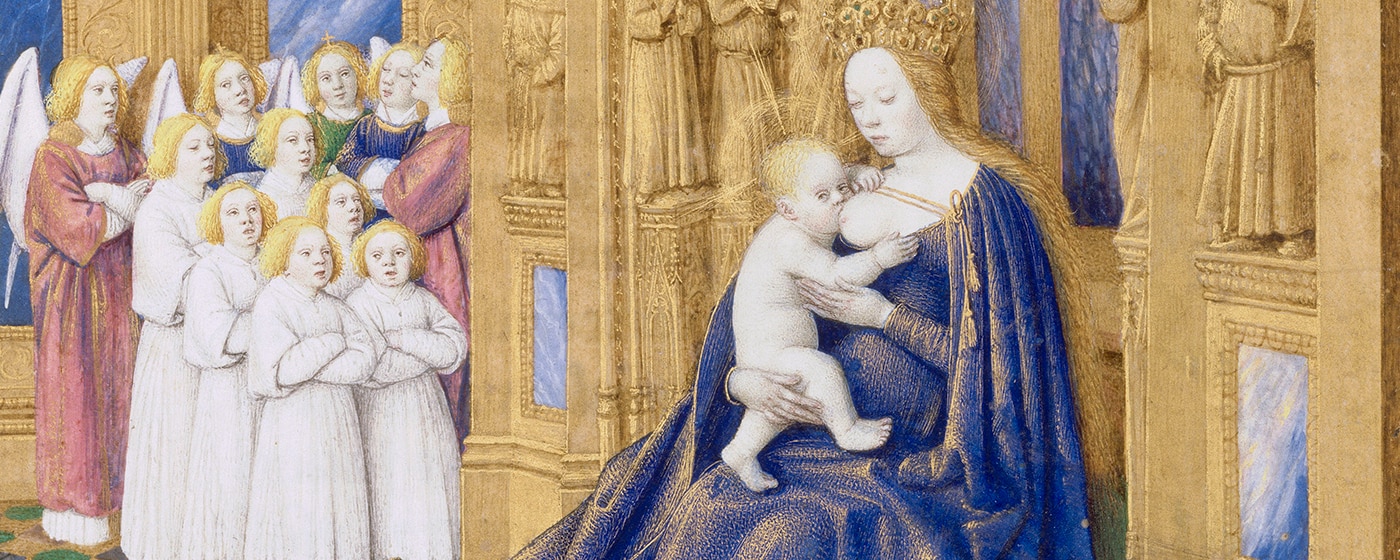

While no canonical gospel alludes to any nursing by the Virgin Mary, this theme was very common between the 14th and 16th centuries. Artists drew inspiration from the apocryphal gospels and used this theme for the purpose of enlightenment(8). However, the symbolism of the Virgin Mary nursing sometimes conveyed unusual societal connotations. This is illustrated in the remarkable right panel of the Melun Diptych, in which Jean Fouquet combined austere sculpturing, vibrant colours and perhaps even a discreet courtyard eroticism. The intense blue and red of the angels and cherubs are set against a Virgin Mary whose face is brought to life by her milky white skin. Her left breast proffered, she and baby Jesus form a pair that one could argue is just as fixed as the ancient representations of Isis nursing Horus, the difference being that Fouquet’s model was not, or not just, a mother goddess. In this panel of the diptych, commissioned by Etienne Chevalier, the treasurer to King Charles VII, he most likely painted Agnès Sorel, the king’s mistress. She was renowned as one of the most beautiful women of her time, closely resembling the Virgin Mary. A strange way of celebrating the humaneness of Jesus by eroticising his mother’s bosom…(9)

One of the most fascinating mysteries of art history surrounds the act of nursing with a storm as backdrop. Here we are dealing with the homeland of colour, the Venice of Titian, at a time of philosophical refinement characteristic of the High Renaissance period, when neoplatonic thought was in fashion. Before long, the Council of Trent (1563) would bring an end to the iconography of the nursing Madonna, condemning images of the Virgin Mary in a state of undress as inappropriate and provocative(10). Prior to this decline, however, Giorgione proved that the theme of concealed nudity could be successfully continued, even when used to convey religious meanings. While The Tempest has baffled experts for almost 500 years – its interpretations have included Moses being saved by the sea while fleeing Egypt, the allegory of Fortitude (the man in Venetian dress) and Charity (the woman), and the representation of the four elements – Philippe Braunstein posits that the painting could in fact show Eve nursing Cain after the fall of man, under the watchful gaze of Adam and of God, whose anger is expressed by the lightning. His interpretation is tantalising and the striking similarities of the painting to a bas-relief by Giovanni Antonio Amadeo (Cappella Colleoni, Bergamo, 1473) are quite convincing(11), even if they do not fully answer the question of Giorgione’s emphasis on nursing. Everything converges: The male figure is overtly gazing upon the child put to the breast; whereas the mother and son in Amadeo’s piece appear to be babbling to one another, forehead to forehead, Giorgione has placed the presumed fratricide Cain’s head at his mother’s breast, while she returns the onlooker’s gaze. There is also the added emotional aspect of an almost imperceptible detail: That of the infant gripping the woman’s left index finger with his right hand. Do such elements hint at a biographical quality? Was Giorgione alluding to his own childhood or to his love for Laura, a young Venetian courtesan? The mystery continues.

At the end of the 16th century, iconology became more widespread, with artists’ repertoires expanding to include symbols, allegories and personification. While Cesare Ripa and his disciples supplied some examples of nudity and nursing (see box), it was not until the 17th and 18th centuries that one area in particular became increasingly popular: Roman charity. Derived from Pliny the Elder, an ‘ancient’ version of the theme of Charity as a theological virtue(12), this episode was a form of glorification of filial piety: Cimon, an elderly Roman man incarcerated and sentenced to death by starvation, is kept alive by the daily visits of his daughter, Pera, who secretly breastfeeds him(13). In Bachelier’s portrayal, in contrast to the frequent tradition of depicting Pera casting nervous looks in the direction of the prison guards out of the picture(14), her posture evokes that of a concerned mother leaning over her infant. Perhaps it was this ambiguity that secretly horrified the French art critic Denis Diderot, even if he pretended otherwise. In any case, he did not hesitate to criticise it harshly(15). Despite the strong symbolic nature of the painting, which transformed breastfeeding into a sacrifice of the self and of life in general, capable even of traversing generations, it did not find favour in Diderot’s eyes.

A male perspective?

The conclusion of this brief overview is that the portrayal of nursing has taken on an ever-increasing number of symbols and mysteries over the years. From its Egyptian origins to the allusive language of iconology, from the idea of human-animal nursing to that of the nursing Madonna, it appears there is an underlying pattern of fascination here, perhaps even a disturbing oddness. Nursing undoubtedly relates back to the most immediate form of survival, even if it did not contribute to the creation of the universe, as numerous mythologies suggest. Yet, it also reveals our animalistic instincts, such as the carnal and prosaic bond that unites mother and child and the eroticism of the female body. Should we interpret this, as in the still-life genre(16), as an effect of the male perspective on an act that is by definition feminine? In other words, does it have a magnifying or distorted mirror effect? At any rate, while nursing is essential in this regard as proof of the perpetuation of the human race, artists portray it as a beautiful enigma, a mystery that may even underlie our modern-day passion for cinema.