Myths about food – fact or fiction?

Food blogs, celebrities and scientists all give advice on healthy diets. It is becoming more and more difficult for consumers to keep track.

©iStock/RyanJLane – Hardly a month goes by without certain foodstuffs or ingredients taking a beating in the media and on social networks.

Sugar, salt and fat – what do these three nutrients have in common? They are all increasingly criticised for being fattening and causing disease. Hardly a month goes by without certain foodstuffs or ingredients taking a beating in the media and on social networks. One of the reasons for this is that, while people in industrial countries are taking more of an interest in the topic of food, they are also overwhelmed by a wealth of information. As Christine Brombach, researcher at the School of Life Sciences at the Zürcher Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften (ZHAW) explained, “When it comes to nutrition, consumers are increasingly looking for easy answers. With this topic, it can be difficult to convert partially contradictory research findings into specific behaviour. Hence, people are more susceptible to simple messages that categorise certain ingredients as ‘good’ or ‘bad’.”

She has observed the growing influence of food bloggers and celebrities who share their eating habits via social media. “If a famous person says, ‘I’ve felt much better since I cut out this ingredient’, that has a greater impact than specialists’ nutritional advice.” Recommendations on blogs and social media often highlight personal experience rather than scientifically proven facts. As a result, an increasing number of people give up gluten or lactose, despite the fact that they do not really need to. Sugar, salt and fat also have a poor reputation, even though science draws varied conclusions. Which current food trends withstand fact checking?

Gluten: The wheat bogeyman

Around 30% of people in the United States are reducing their consumption of products that contain gluten1 – a protein found in wheat, rye, spelt and barley. The global turnover from gluten-free food doubled between 2007 and 2013, to reach 2.1 billion dollars.2 However, only an estimated 1% of people in the United States and Europe suffer from gluten intolerance.3 People in this group usually suffer from coeliac disease, an autoimmune disorder where the consumption of products containing gluten damages the mucous membrane in the small intestine, thus diminishing the absorption of nutrients. Other symptoms include fatigue and headaches.

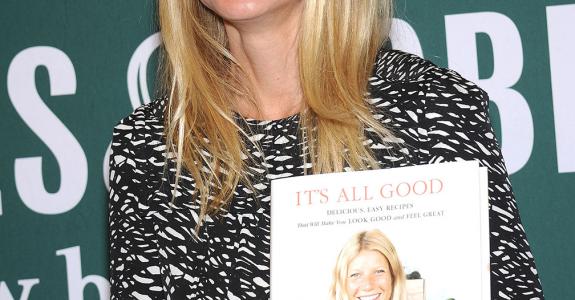

So why do more and more people swear by a gluten-free diet? According to Christine Brombach, “Stars such as the American actress Gwyneth Paltrow say that they have felt much better and happier since they cut out gluten. Also, especially in German-speaking areas, books such as Dumm wie Brot [Grain Brain] and Weizenwampe [Wheat Belly] have contributed to the association of consumption of this protein with mental fatigue and being overweight.” She adds that the gluten content in industrially produced bread, for example, has drastically increased over the last fifty years, as this makes the dough rise faster. However, there is no scientific proof of the damaging influence of gluten on the human body, nor of the positive effects of avoiding gluten – except for those people who actually suffer from gluten intolerance.4

Lactose: Improved digestion without milk

Just as with gluten, many consumers cut out lactose (milk sugar) despite there being no scientific proof of it being harmful – except in the case of lactose intolerance. People with lactose intolerance lack lactase, the enzyme that is responsible for the dissociation of lactose. If milk sugar is not broken down, bacteria in the large intestine ferment it, which may result in flatulence, stomach ache and other symptoms. In Germany, for example, according to a survey by the Landesvereinigung Milch5 [State Association for Milk] approximately 15% of the population suffer from lactose intolerance, yet around 40% regularly consume lactose-free products.

“Like gluten, lactose has become associated with diffuse discomfort – such as headaches and fatigue”, remarked Christine Brombach. However, there is no scientific proof of this correlation. In fact, lactose-free products may even contain around 100 mg of lactose per 100 g of food – as much as in many varieties of cheese.6 An article published in 2000 in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics revealed that, even people with lactose intolerance can begin to process a dairy-rich diet when this is gradually introduced over several weeks.7

Fat: Does what it says

For a long time, it was assumed that too much fat in a diet leads to being overweight and developing arterial sclerosis. Nowadays, research approaches the topic very differently: The decisive factor is not the amount of fat a person consumes, but rather what kind of fat. We now differentiate between saturated fats – mainly found in dairy products and meat –, monounsaturated fats – in products such as nuts, olive oil and avocados – and polyunsaturated fats. The latter are mainly found in rapeseed, sunflower, soya and linseed oils. Christiana Gerbracht of the German Institute of Human Nutrition pointed out that “Fat is the nutrient that gives the body the most energy. Alongside this quality, fats have other positive effects on the human body: polyunsaturated fats prevent cholesterol from reaching excessive levels, which can in turn prevent arterial sclerosis”. Besides, there is no scientific proof whatsoever of the detrimental effect of saturated fats. Contrary to popular belief, they do not lead to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.8

In 2016, the Universitat de Barcelona announced the results of its much-discussed study, which demonstrated that a Mediterranean diet with increased amounts of plant-based fat reduces body weight more than a low-fat diet does.9 Tim Spector, Professor of Genetic Epidemiology at King’s College London, came to a similar conclusion. In his book The Diet Myth: The Real Science Behind What We Eat, published in 2015, he explains that slim and healthy people have more intestinal bacteria. To encourage such bacteria to develop, he recommends a balanced diet that expressly includes products containing fats.10

Sugar: The white killer

Is sugar as dangerous as tobacco and alcohol? An increasing number of people believe this to be the case. In 1972, in his bestseller Pure, White and Deadly, the American researcher John Yudkin already warned of the dangers of sugar.11 Since 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended that sugar should account for only 10% of daily calorie requirements, which translates to 50 g or twelve teaspoons. The Geneva-based organisation recommends that, in future, this amount be reduced to 5%. This concerns the sugar mixed into meals and drinks as well as that contained in honey, cordials and fruit juices. The ambitious nature of this recommendation becomes clear when you consider that one can of lemonade or orange juice alone contains an average of ten teaspoons of sugar.12

Even though no expert today would recommend a high consumption of sugar, it is also important to consider this ingredient in a broader context. According to Christiana Gerbracht, cutting out sugar cannot compensate for an unbalanced diet or a lack of exercise. She added that, “The brain requires a certain amount of glucose. In addition, when the food industry uses stevia as a substitute sweetener, sugar is often added to improve the taste.”

Salt: Warning! High blood pressure!

Mankind has used table salt for over 5000 years. Even the Sumerians used salt to preserve food. The ingredient was so sought-after that Roman legionaries were paid in salt. In the Middle Ages, it became known as “white gold”.13 What about today? There is some disagreement about the levels of salt that are damaging for the human body. On the one hand, there are studies that show that higher salt consumption leads to raised blood pressure, which can cause strokes and heart failure. The reason for this is that salt retains water in the body, which leads to the heart having difficulty pumping blood. Consequently, blood pressure increases.

On the contrary, however, other recent studies have shown that insufficient salt consumption can increase the risk of heart failure, as it leads to a release of hormones that cause blood pressure to rise.14 The fact is, salt is absolutely necessary for many of our bodily functions, such as regulating the acid-alkaline balance. As Christine Brombach from the ZHAW explained, “Admittedly, industrial food production currently uses too much salt. The WHO recommends an allowance of 5 g of salt a day, which roughly translates to a teaspoon. Those who rarely eat ready meals and use little salt when cooking, run little risk.”