-

Visit

Opening hours From Tuesday to Sunday

October to March:

10:00 - 17:00

April to September:

10:00 - 18:00Contact emailEntrance feesAdults: CHF 15.00

Reduced rate: CHF 12.00

Children 6-15: CHF 6.00

Children 0-5: FreeAddressQuai Perdonnet 25

CH-1800 Vevey

Switzerland - Learn & Play

- About us

- Accessibility

Welcome !

Think. Learn. Interact.

Create an account in seconds and discover the amazing Alimentarium experience !

- Home

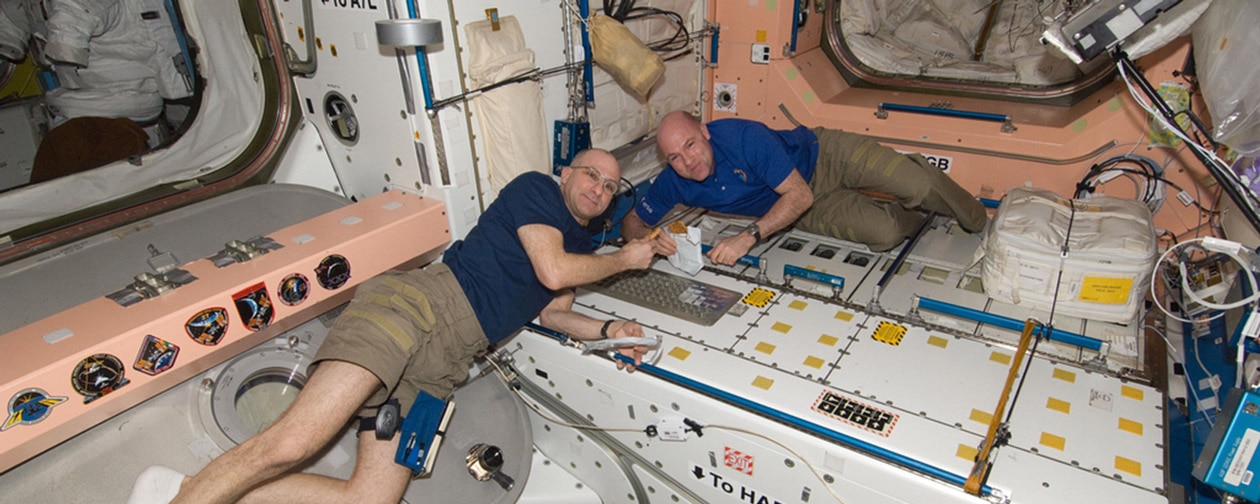

- Brief History of Eating In Space

more...

alimentarium

magazine

Our monthly newsletter keeps you up-to-date so you can be the first to discover our latest articles and videos. Explore, learn and join in!