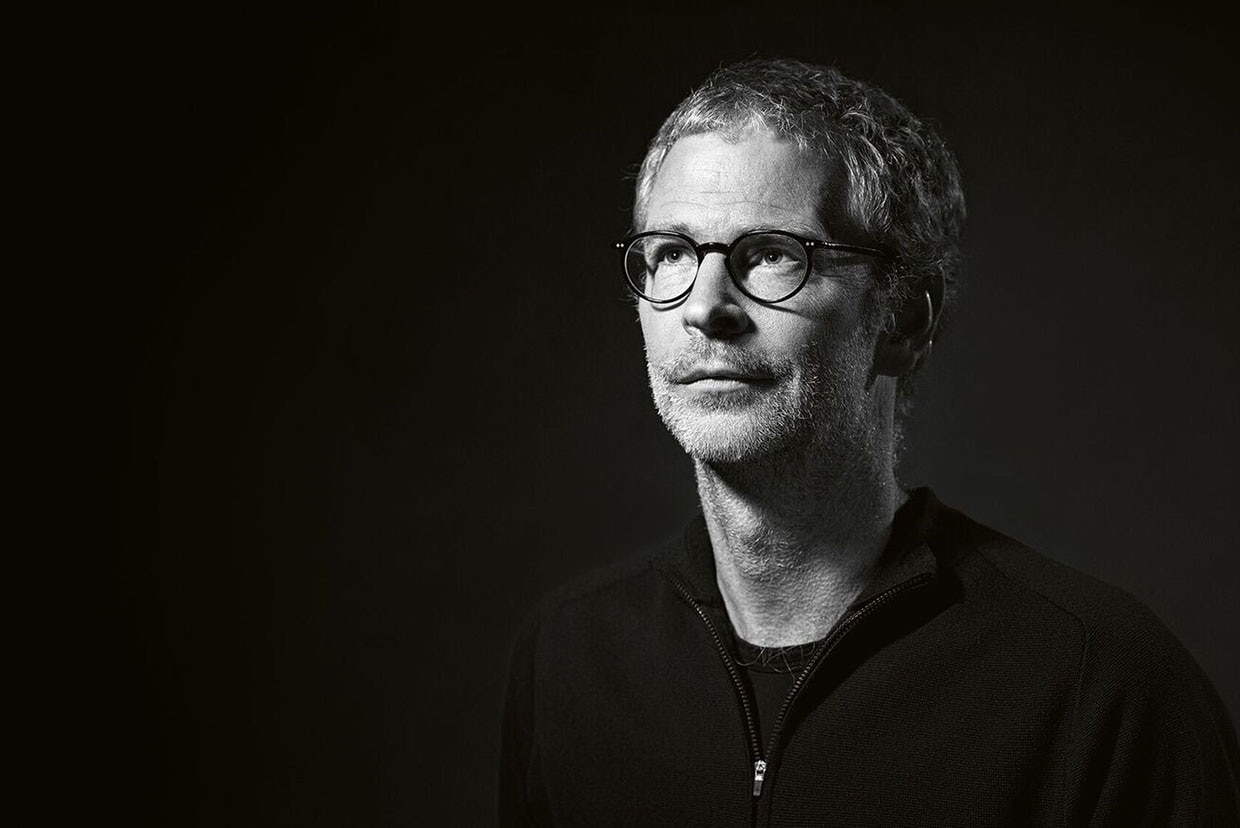

Music of the vines

With his feet firmly in the soil and his head in the clouds, this curious Protestant hedonist sculpts high-quality wines.

Bottles ready for labelling look like the keys of an organ of flavours celebrating the terroir... ©Christophe Schenk

Lying in a cleft in the rocky foothills bordering Villeneuve, Christophe Schenk’s wine cellar has something of an eagle’s nest about it. For lovers of good wine, it is a secret whispered from ear to ear. Christophe Schenk is a veritable one-man-orchestra at the head of this family wine estate. To say that he can “hum the tune” barely does him justice: Both a winemaker and founder of the association contrepoint, which organises classical music concerts, he seems totally gripped by his passion for harmony and creativity. Yet his approach to the land is no gentleman farmer’s whim. He is not a dilettante tinkering with his vines, but an astute technician, an intransigent observer of soil and grape varieties. He knows how to enhance the terroir to express its particular qualities. Hence, his 2013 Chasselas Grand Cru (AOC Chablais-Villeneuve) received the honour of high praise from Robert Parker, one of the most influential wine critics. Meet this adoptive Vaudois winegrower who was kind enough to not just open up his wine cellar for us, but also his heart.

The estate is the fruit of a rather singular family history. Can you tell us about it?

Conventional viticulture, organic grapevines, or a biodynamic approach: What’s your school of thought?

Since 2006, all the grapevines on the plots I’m in charge of have been cultivated organically, only using sulphur and moderate amounts of copper. However, the estate doesn’t meet all the criteria for biodynamic viticulture. I definitely pay attention to the phases of the moon and take inspiration from forestry, but I’m happy to give unicorn horn powder or other esoteric ingredients a miss... In general, I would say it’s best to go easy on treatments: Grapevines are robust plants so, in my opinion, they must suffer a little in order to give their best and to express the quintessence of the soil.

What are your favourite grape varieties?

It’s hard to say, there’s such choice! If I had to choose though, I must admit that I have a particular sweet spot for the Mondeuse, a simple variety well adapted to organic cultivation, and charmingly unrefined. I also like working with Sauvignon Blanc, although it’s quite tricky to vinify, and our “national” Chasselas, also rather complicated, atypical, very delicate and low in alcohol – a variety that’s harder to cultivate organically, because it responds well to a bit of pampering.

Which ones would you love to cultivate?

First of all, Completer, a grape variety from the canton of Grisons whose name refers to the Latin completorium, or compline in English, in Catholic liturgy the last prayer service of the day after vespers. Unfortunately, it wouldn’t work in our region. Then there’s Cornalin, which could produce something unusual and unexpected if I worked on it on the estate.

Which two wines are your pride and joy?

Each vintage is different, so preferences vary from year to year. Generally speaking though, I have a certain weak spot for Névés, a non-malo2 Chasselas (AOC Chablais/Villeneuve), as well as for Hautes côtes de lune, a Pinot Noir Grand Cru that could almost console you for “the trouble with being born”3 (AOC Côtes-de-l'Orbe/Chamblon)...

Non-malo wines are one of the estate’s specialities. Are there others?

In terms of fermentation, a few years ago I started something new with the reds. We used to cool the must to 5°C for it to start macerating. Now I ferment it at room temperature. As I work with natural yeasts, cold fermentation could make my must go in the wrong direction, while the ambient temperature suits the natural cycle of the grapes better.

Besides your love of the vineyard, you’re also a music lover and artistic director of the association contrepoint. Which classical pieces would ideally accompany the two wines you just mentioned?

For Hautes côtes de lune, any Schubert lied would do the trick! Meanwhile, the Névés carries me off to Gaspard de la nuit (a work by Aloysius Bertrand) and in particular to Ondine, the first of the three poems Ravel set to music.

Since it’s a current topic, what are your thoughts about the Fête des Vignerons?

You can only admire the power of collective enthusiasm. It makes this tradition a contemporary creation in tune with this day and age. In my opinion, however, we should be able to question the event’s tendency towards gigantism, without being called a spoilsport. Other than this slight doubt, I don’t deny how much pleasure it gives me. For such an ‘old’ profession rooted in a terroir and in regional memory to be placed in the limelight once in a generation is a tribute worth celebrating! Now it’s up to the ninety or so winemakers of the Confrérie and to all the others, who are at least as numerous in the canton of Vaud, to prepare for the future, to adapt winegrowing to tomorrow’s environmental and commercial challenges.