The yin and yang of hunger

What is it exactly that makes us feel hungry? And what are the mechanisms that tell us we’ve eaten enough? Science has taken huge strides forward in understanding the processes that maintain a healthy balance between food intake and energy expenditure … and what to do when things go wrong.

We all need food. It’s what gives us the energy to live our daily lives, keeps us healthy, and brings us pleasure. But what is it exactly that tells us when to eat and, just as importantly, when to stop? These are questions which scientists around the world are working to answer.

And it’s important they do. Because obesity is an increasing problem across the globe. There are all sorts of reasons why people over-eat. But that’s only half the story.

Our weight is regulated by two principal factors:

- energy in – in the form of the food and drink we consume; and

- energy out – the extent to which we burn off that energy through exercise and daily living, and to maintain our body temperature and keep our organs functioning.

‘Energy homeostasis’ is the balance between the energy we take on board (calories, fat, protein, etc) and the energy we expend through physical activity and to maintain the basic metabolic rate we all need to survive. Get it right and we maintain our correct body weight for optimal physical and mental functioning. But if we don’t achieve energy homeostasis, it can make us underweight in the case of insufficient energy intake or, more commonly, overweight, when ‘energy in’ exceeds ‘energy out’.

So far, so good – it’s basic common sense. But understanding the science behind the simple facts is far more complicated. Our appetite and feelings of satiety result from complex interactions of signals which constantly pass between stomach and brain, regulating food intake. Our understanding of how the body works has increased dramatically over recent decades, especially with the arrival of genetics. And one of the major breakthroughs as far as understanding hunger is concerned is the discovery of the ‘hunger hormone’ ghrelin.

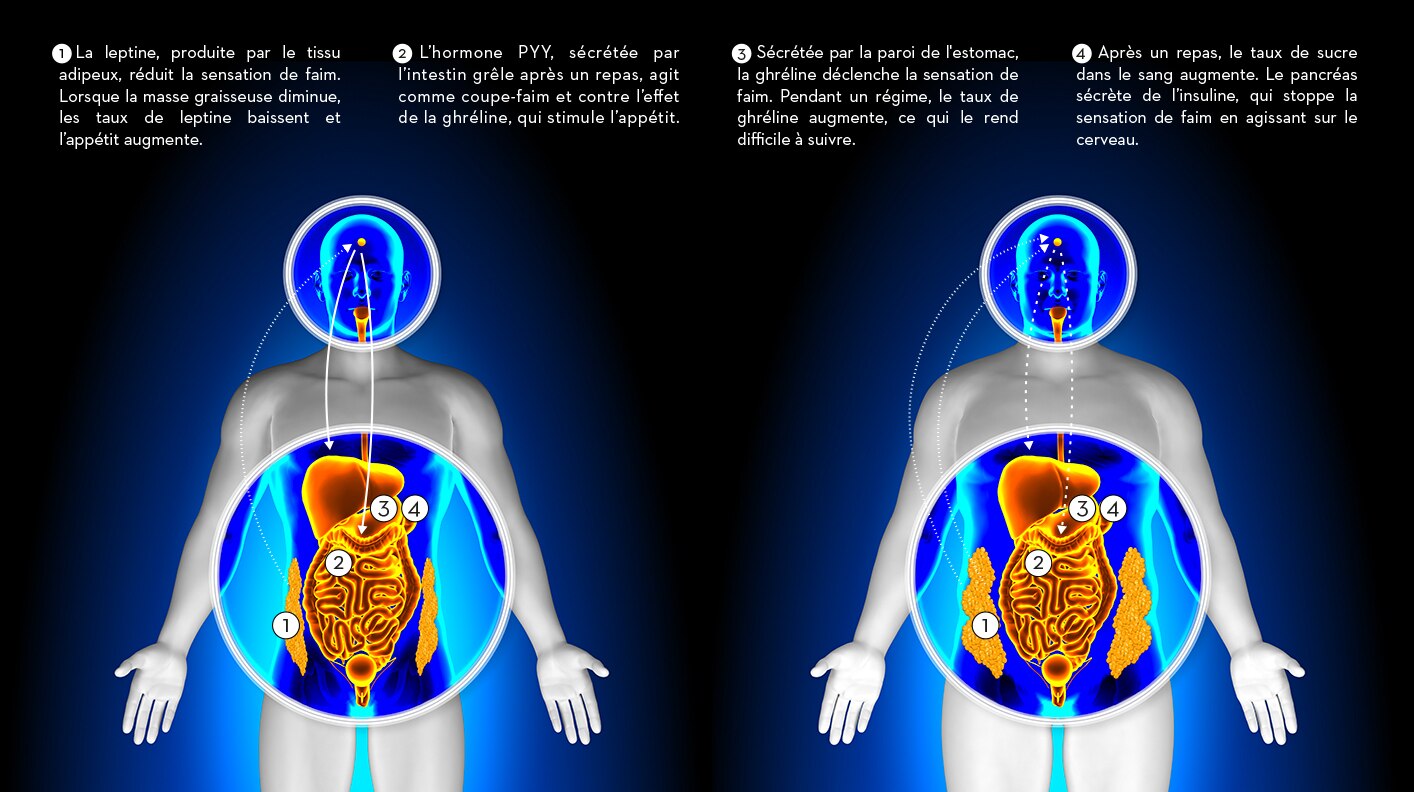

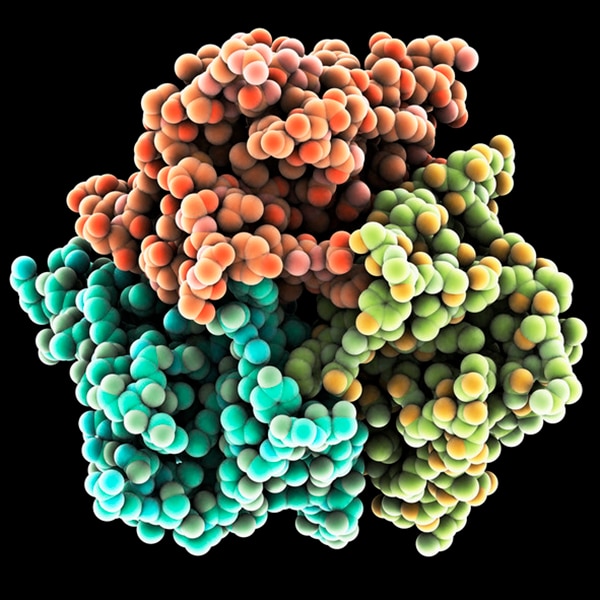

Ghrelin is a peptide produced by certain cells in the stomach, which sends messages to the brain via the peripheral nervous system and blood stream. As well as controlling hunger, it also plays a significant role in regulating the distribution and rate at which we use energy and store fat, and is thus an important factor governing body weight and energy balance.

Ghrelin is continuously secreted, but when the stomach is empty, its secretion increases. When the stomach is stretched (ie full of food), secretion is reduced. It acts on hypothalamic brain cells to signal increased hunger and the secretion of gastric acid to prepare our bodies to take in food.

There’s a specific receptor in the brain to receive this ‘hunger message’. This ghrelin receptor is also found on some of the cells that express the receptor for leptin, a ‘satiety hormone’ which has the opposite effect to ghrelin. So these brain cells effectively receive and process the messages produced by the body which tell it when we need to eat, and when we should stop, showing just how complicated the system of regulating our energy homeostasis is.

This communication between stomach and brain involves many different signalling pathways, not all of which are well understood yet. But what we do know is that, in addition to regulating the hunger we feel, ghrelin also plays an important role in controlling the pleasure we derive from eating and drinking, with ghrelin levels peaking just before a meal, and at their lowest immediately after.

On the other side of the ‘hunger/satiety equation’ is an array of gastrointestinal hormones responsible for reducing appetite. These include leptin, a satiety hormone mainly secreted from fat cells. Together, they counteract ghrelin’s effect of increasing our desire to eat. As explained above, leptin and ghrelin are closely interlinked, inhibiting and promoting hunger and regulating our fat stores in line with our bodies’ changing requirements.

Leptin’s role is to promote satiety. People suffering from obesity show a decreased sensitivity to leptin, leading to an inability to detect satiety despite their high energy stores. Or in other words, their bodies don’t tell them when to stop eating.

Leptin levels are generally higher in obese than normal-weight individuals. The problem here often stems from their resistance to leptin (rather like insulin resistance in those suffering from type 2 diabetes), although the precise causes of this resistance are not yet fully understood. Not unexpectedly, absence of leptin or its receptor in the brain leads to uncontrolled hunger and obesity.

There’s still much to learn before we fully comprehend the mechanisms of hunger and satiety. Leptin was only discovered in 1994, with ghrelin’s discovery following five years later. Fully understanding the role played by leptin is complicated by the fact it interacts with numerous other regulators of satiety, while although ghrelin is the only hunger regulator identified so far, that’s not to say there aren’t others waiting to be discovered.

Then there are the various other factors influencing our eating habits. There’s our preference for energy-dense, high-calorie food containing excess amounts of sugar and fat, and often eaten for pleasure rather than because we’re hungry, for example. Taken in combination with general levels of education and availability of healthy eating advice, along with environmental factors and lifestyle choices such as sedentary office work and access to exercise facilities, they all have a major impact on our ‘energy in, energy out’ equation. But understanding the mechanisms that drive hunger and satiety is opening up new avenues of research and development of healthier food and therapies to help those who struggle to control their calorie intake and maintain the correct ‘energy homeostasis’.

There are many different reasons why we eat what we eat, and in what amounts. But the better science understands the drivers behind those decisions, the better able we’ll all be to make the choice that’s right for us, and master our own ‘hunger hormone’.