Tea, a source of longevity

Soon after tea was discovered, it featured in the Chinese pharmacopoeia as a remedy for various ailments. Some also believed it was able to slow down the ageing process or bestow immortality on humanity. In Europe, tea could supposedly prevent gout, and some doctors even deemed it a ‘divine’ drink. Today, packaging continues to extol the advantages of these same ‘legendary’ qualities, while science only partially substantiates them.

This ‘divine herb’, an elixir of immortality

Various Chinese legends narrate the discovery of tea as a plant full of goodness. According to one such legend, Emperor Shen Nong, who reigned from 2737 to 2697 BCE, discovered tea while searching for a remedy for a fatal epidemic that was sweeping through the country. He tasted 72 kinds of plants, including tea leaves, which made his body clear and transparent. The first written sources, which date back to the 1st century BCE, refer to Lao Tzu, the founder of Taoism, and describe tea as an elixir of immortality.

Under the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE), Taoist and Buddhist monks adopted tea. They appreciated this beverage as it helped them stay awake during long sessions of meditation. At this time, between the years 760 and 780, the Chinese philosopher Lu Yu wrote the first book devoted entirely to tea, Chá jīng, or The Classic of Tea. He presented different aspects of the drink, including those relating to health: It was advised to drink tea if suffering from dry eyes, aching joints or chest pains. However, to be effective, Lu Yu insisted on the importance of the quality of the tea. Picked in the wrong place or at the wrong time, prepared without due care and attention or with the wrong herbs, tea could cause illnesses. The water used to prepare it also played a crucial role, the best being mountain water, and especially that which dripped from stalactites – another very popular remedy favouring longevity. Lu Yu also quoted a hermit by the name of Hu, according to whom the prolonged consumption of bitter tea would transform a human being into a winged being, in other words, into an immortal being.

In Japan, tea fascinated the Zen priest Eisai (1141-1215), so much so that he wrote Kissa Yôjôki or How to Stay Healthy by Drinking Tea. For him, the benefits of the drink were indisputable; tea was an elixir for preserving health and prolonging life in old age. Poems also sang the praises of tea. The famous Seven Bowls of Tea by the Chinese poet Lu Tong was very popular in Japan, where it apparently served as one of the foundations of the tea ceremony. In this poem, each bowl has a specific effect (soothing, purifying, refreshing, etc.) and the sixth unites the poet with the immortals.

In Europe, despite some detractors, tea was seen as an exceptionally wholesome drink. Jesuit explorers and missionaries wrote that tea was ‘extremely healthy’ and would slow down the ageing process and prevent gout. Doctors were also convinced by its virtues. This exotic drink fascinated Europe and written works sang its praises. In 1659, the doctor Denis Joncquet described tea as a ‘divine herb’ and likened it to ambrosia.

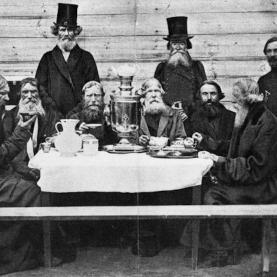

Later, tea drinking became widespread and its medicinal use gave way to drinking tea for pleasure. In the 19th century, while in France tea was still reserved for ladies frequenting high-society salons, the entire population of the United Kingdom was enamoured with the drink, consuming more than 30 million kilograms a year.

The benefits of tea according to current scientific studies

Nowadays, tea as a source of longevity has become a selling point. Various brands promote its wholesome qualities to satisfy consumers who are increasingly concerned about their wellbeing and the environment. Chinese medicine still considers green tea as a nurturing drink and it is credited as one of the keys to the high life expectancy of the Japanese. Few scientific studies confirm a direct effect on long-term health and longevity. Tea is nevertheless rich in polyphenols and catechins, chemical compounds with antioxidant properties. By reducing oxidative stress, which damages cells, they are thought to prevent or slow down the onset of certain conditions, notably cardiovascular diseases.

CHA SANGMANEE, Kitti, DONZEL, Catherine, MELCHIOR-DURAND, Stéphane, STELLA, Alain, 1996. L’ABCdaire du thé. Paris : Flammarion.

YiI, Sabine, JUMEAU-LAFOND, Jacques, WALSH, Michel, 1990. Le livre de l’amateur de thé. Paris : Robert Laffont.

PERRIER-ROBERT, Annie, 1999. Le thé. Paris : Éditions du Chêne.

BUTEL, Paul, 1989. Histoire du thé. Paris : Éditions Desjonquères.

TOUSSAINT-SAMAT, Maguelonne, 1997. Histoire naturelle et morale de la nourriture. France : Larousse.

YU, Lu, 2015. Le classique du thé. Paris : Éditions Payot & Rivages

VITAUX, Jean, 2009. La mondialisation à table. Presses Universitaires de France : Paris.

HIGDON, Jane V., FREI, Balz, 2003 Tea Catechins and Polyphenols: Health Effects, Metabolism, and Antioxidant Functions, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 43:1, 89-143, DOI: 10.1080/10408690390826464

PETERS, Ulrike, POOLE, Charles, et ARAB, Lenore, 2001, Does tea affect cardiovascular disease? A meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 2001, vol. 154, no 6, p. 495-503. DOI:10.1093/aje/154.6.495

https://academic.oup.com/aje/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/aje/154.6.495

ONAKPOYA, Igho, SPENCER, E., HENEGHAN, C., et THOMPSON, M., 2014, The effect of green tea on blood pressure and lipid profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases, 2014, vol. 24, no 8, p. 823-836. DOI:10.1016/j.numecd.2014.01.016